Wind Energy Guidelines: Science and Collaboration at Work, Every Day

On the computer screen, Rene Braud and her Development Team zoom in on several square miles of agricultural land in Texas where their company, Pattern Energy, is looking at early development for a wind energy project. Then Braud, Director of Environmental Policy and Compliance, points to a pocket of wetlands, about ten miles away, where threatened and endangered wildlife potentially could be present. The question now is: What site-specific due diligence should the team undertake to make sure the project is sited responsibly?

Decisions about wind turbine siting and operations come up every day. To inform decision-making and ensure that the nation’s increased use of wind energy successfully coexists with birds, bats, and other wildlife, a collaborative process that may be unique in the world of energy has come together, and grows today. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (USFWS) Land-Based Wind Energy Guidelines was a milestone in that process, and continue to help companies like Pattern navigate responsible development of wind projects.

A Big Win for Wildlife and Clean Energy

When the USFWS proposed guidelines for developing wind energy in the early 2000s, wind energy companies and conservation groups joined forces to help accomplish the desired conservation outcomes.

By that time, many in the conservation and wind energy industry communities had been seeking for over a decade to better understand the potential impacts of wind turbines on wildlife. These groups and companies encouraged the USFWS to build on the science already learned through initiatives such as the U.S. Department of Energy-funded National Wind Coordinating Collaborative and the Bat and Wind Energy Cooperative, and to convene a dialogue in an unprecedented approach.

In 2007, the Secretary of Interior established a Federal Advisory Committee to develop recommendations to guide developers to minimize impacts of wind turbines on wildlife. The committee included representatives from federal and state agencies, the wind energy industry, conservation community, scientists, and tribes. The committee’s intense and focused work resulted in consensus recommendations that were largely adopted by the USFWS in the final Wind Energy Guidelines published in 2012. The guidelines were hailed as a “game-changer” and a “big win for both wildlife and clean energy.”

Taking Action Based on Risk

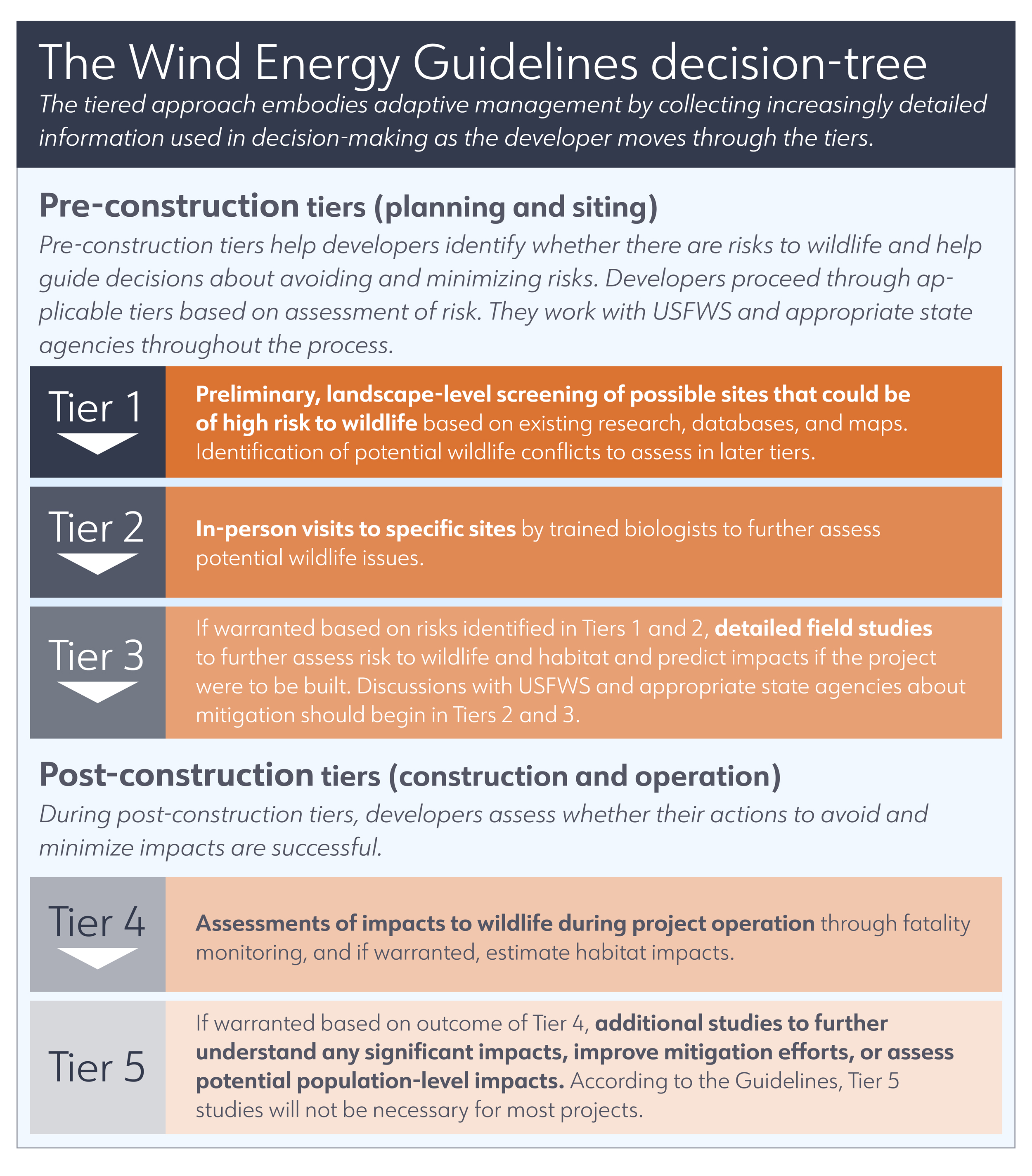

The voluntary Land-Based Wind Energy Guidelines feature a “tiered,” decision-tree approach. The underlying principle recognizes that the level of due diligence and investment in studying and preventing impacts should be based on the level of risk posed by a project.

“The Guidelines help developers work through decisions,” said Braud, who served on the Federal Advisory Committee. “If you have a potential project site in an area where a number of species may pass through, the next question is, how do you assess and address the actual level of risk? The Guidelines are designed to address this type of question. They outline best practices not only for siting, but for construction, operation, retrofitting, repowering, and decommissioning wind energy projects.”

An additional outcome of the Guidelines is the attention to certain bats, non-migratory birds, and other species that may be of concern but are not federally protected.

“The Guidelines broke ground where there was no legal requirement,” said Sam Enfield, Director of MAP Royalty, and a member of the Federal Advisory Committee.

A Milestone for Collaboration

Development of the Guidelines was the outcome of unprecedented collaboration.

“By collaborating with conservationists instead of slugging it out, the wind power industry gains vital support to expand and create jobs, and wildlife gets the protection crucial for survival,” said David Yarnold, President & CEO of Audubon, when the Guidelines were released.

“Everyone was willing to listen to one another and to advocate in good faith for what we cared about,” said Aimee Delach, a member of the Federal Advisory Committee at the time for Defenders of Wildlife and now Senior Policy Analyst for Climate and Conservation at Defenders, looking back at the process today.

“This in turn built trust and ultimately made it possible to identify and agree on recommendations that were both science-based and practicable, and that balanced the urgent need to build a sustainable energy future with the ongoing need to minimize adverse impacts to wildlife and habitat.”

Continuing Collaboration on Solutions

At about the same time as development of the Guidelines was under way, leaders in the wind energy industry and conservation and scientific communities saw the need for an independent forum where – together – they could advance effective solutions and look at the future.

As a result, AWWI was born. Today, AWWI’s programs encompass basic research, advanced approaches to understand risk, innovation and evaluation of technology solutions, eagle conservation initiatives, and much more. AWWI celebrates its 10th Anniversary this year.

“The Wind Energy Guidelines are a living process, in our experience,” says Jenni Dean, Vice President of Environmental & Permitting at Tradewind Energy, one of the companies that partners with AWWI. “Tradewind is a utility-scale developer of quality wind and solar power projects, and for us, conservation and respect for environment and community are an integral part of that quality. Every day, the give and take in the field between research and decision-making is strengthened by the collaborative work of the wind energy industry and conservation and scientific organizations on many fronts, from bat research to technological innovation. We are proud to be part of that collective endeavor.”

“The collaborative process and the dedication that drive the wind-wildlife community generate a powerful synergy,” said Braud. “The Wind Energy Guidelines create an overall risk assessment framework and help companies design studies and incorporate research to better understand questions in each tier. Initiatives such as AWWI’s eagle program focus on specific species or issues. At the hub, AWWI works as a catalyst to support the collaborative process, generate the necessary science, and develop solutions. In the end, it’s all about effective solutions that promote clean energy and conserve wildlife.”